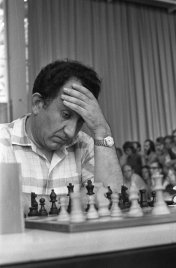

Tigran Petrosian

Friday, July 26, 2024

Tigran Vartanovich Petrosian (June 17, 1929 – August 13, 1984) was a Soviet Armenian Grandmaster, and World Chess Champion from 1963 to 1969. He was nicknamed "Iron Tigran" due to his almost impenetrable defensive playing style, which emphasized safety above all else. Petrosian is credited with popularizing chess in Armenia.

Petrosian was a Candidate for the World Chess Championship on eight occasions (1953, 1956, 1959, 1962, 1971, 1974, 1977 and 1980). He won the World Championship in 1963 (against Mikhail Botvinnik), successfully defended it in 1966 (against Boris Spassky), and lost it to Spassky in 1969. Thus he was the defending World Champion or a World Championship Candidate in ten consecutive three-year cycles. He won the Soviet Championship four times (1959, 1961, 1969, and 1975).

Petrosian was born to Armenian parents on June 17, 1929 in Tiflis, Georgian SSR (modern-day Georgia). As a young boy, Petrosian was an excellent student and enjoyed studying, as did his brother Hmayak and sister Vartoosh. He learned to play chess at the age of 8, though his illiterate father Vartan encouraged him to continue studying, as he thought chess was unlikely to bring his son any success as a career. Petrosian was orphaned during World War II and was forced to sweep streets to earn a living. It was about this time that his hearing began to deteriorate, a problem that afflicted him throughout his life. In a 1969 interview with Time magazine, he recalled:

He used his rations to buy Chess Praxis by Danish grandmaster Aron Nimzowitsch, a book which Petrosian later stated had the greatest influence on him as a chess player. He also purchased The Art of Sacrifice in Chess by Rudolf Spielmann. The other player to have had an early effect on Petrosian's chess was José Raúl Capablanca. At age 12 he began training at the Tiflis Palace of Pioneers under the tutelage of Archil Ebralidze. Ebralidze was a supporter of Nimzowitsch and Capablanca, and his scientific approach to chess discouraged wild tactics and dubious combinations. As a result, Petrosian developed a repertoire of solid positional openings, such as the Caro–Kann Defence. After training at the Palace of Pioneers for just one year, he defeated visiting Soviet grandmaster Salo Flohr at a simultaneous exhibition.

By 1946, Petrosian had earned the title of Candidate Master. In that year alone, he drew against Grandmaster Paul Keres at the Georgian Chess Championship, then moved to Yerevan where he won the Armenian Chess Championship and the USSR Junior Chess Championship. Petrosian earned the title of Master during the 1947 USSR Chess Championship, though he failed to qualify for the finals. He set about to improve his game by studying Nimzowitsch's My System and by moving to Moscow to seek greater competition.

Grandmaster in Moscow

After moving to Moscow in 1949, Petrosian's career as a chess player advanced rapidly and his results in Soviet events steadily improved. He placed second in the 1951 Soviet Championship, thereby earning the title of international master. It was in this tournament that Petrosian faced world champion Botvinnik for the first time. Playing White, after obtaining a slightly inferior position from the opening, he defended through two adjournments and eleven total hours of play to obtain a draw. Petrosian's result in this event qualified him for the Interzonal the following year in Stockholm. He earned the title of Grandmaster by coming in second in the Stockholm tournament, and qualified for the 1953 Candidates Tournament.

Petrosian placed fifth in the 1953 Candidates Tournament, a result which marked the beginning of a stagnant period in his career. He seemed content drawing against weaker players and maintaining his title of Grandmaster rather than improving his chess or making an attempt at becoming World Champion. This attitude was illustrated by his result in the 1955 USSR Championship: out of 19 games played, Petrosian was undefeated, but won only four games and drew the rest, with each of the draws lasting twenty moves or less. Although his consistent playing ensured decent tournament results, it was looked down upon by the public and by Soviet chess media and authorities. Near the end of the event, journalist Vasily Panov wrote the following comment about the tournament contenders: "Real chances of victory, besides Botvinnik and Smyslov, up to round 15, are held by Geller, Spassky and Taimanov. I deliberately exclude Petrosian from the group, since from the very first rounds the latter has made it clear that he is playing for an easier, but also honourable conquest—a place in the interzonal quartet."

This period of complacency ended with the 1957 USSR Championship, where out of 21 games played, Petrosian won seven, lost four, and drew the remaining 10. Although this result was only good enough for seventh place in a field of 22 competitors, his more ambitious approach to tournament play was met with great appreciation from the Soviet chess community. He went on to win his first USSR Championship in 1959, and later that year in the Candidates Tournament he defeated Paul Keres with a display of his often-overlooked tactical abilities. Petrosian was awarded the title of Master of Sport of the USSR in 1960, and won a second Soviet title in 1961. His excellent playing continued through 1962 when he qualified for the Candidates Tournament for what would be his first World Championship match.

After playing in the 1962 Interzonal in Stockholm, Petrosian qualified for the Candidates Tournament in Curaçao along with Pal Benko, Miroslav Filip, Bobby Fischer, Efim Geller, Paul Keres, Viktor Korchnoi, and Mikhail Tal. Petrosian, representing the Soviet Union, won the tournament with a final score of 17½ points, followed by fellow Soviets Geller and Keres each with 17 points and the American Fischer with 14. Fischer later accused the Soviet players of arranging draws and having "ganged up" on him to prevent him from winning the tournament. As evidence for this claim, he noted that all 12 games played between Petrosian, Geller, and Keres were draws. Statisticians pointed out that when playing against each other, these Soviet competitors averaged 19 moves per game, as opposed to 39.5 moves when playing against other competitors. Although responses to Fischer's allegations were mixed, FIDE later adjusted the rules and format to try to prevent future collusion in the Candidates matches.

Having won the Candidates Tournament, Petrosian earned the right to challenge Mikhail Botvinnik for the title of World Chess Champion in a 24-game match. In addition to practicing his chess, Petrosian also prepared for the match by skiing for several hours each day. He believed that in such a long match, physical fitness could become a factor in the later games. This advantage was increased by Botvinnik being much older than Petrosian. Whereas a multitude of draws in tournament play could prevent a player from taking first place, draws did not affect the outcome of a one-on-one match. In this regard, Petrosian's cautious playing style was well-suited for match play, as he could simply wait for his opponent to make mistakes and then capitalize on them. Petrosian won the match against Botvinnik with a final score of 5 to 2 with 15 draws, securing the title of World Champion.

Reigning World Champion

Upon becoming World Champion, Petrosian campaigned for the publication of a chess newspaper for the entire Soviet Union rather than just Moscow. This newspaper became known as 64. Petrosian studied for a degree of Master of Philosophical Science at Yerevan State University; his thesis, dated 1968, was titled "Chess Logic, Some Problems of the Logic of Chess Thought".

In 1966, three years after Petrosian had earned the title of World Chess Champion, he was challenged by Boris Spassky. Petrosian defended his title by winning rather than drawing the match, a feat that had not been accomplished since Alexander Alekhine defeated Efim Bogoljubov in the 1934 World Championship. However, Spassky would defeat Efim Geller, Bent Larsen, and Viktor Korchnoi in the next candidates cycle earning a rematch with Petrosian, at Moscow in 1969. Spassky won the match by 12½–10½.

Later career

Along with a number of other Soviet chess champions, he signed a petition condemning the actions of the defector Viktor Korchnoi in 1976. It was the continuation of a bitter feud between the two, dating back at least to their 1974 Candidates semifinal match in which Petrosian withdrew after five games while trailing 3½–1½ (+3−1=1). His match with Korchnoi in 1977 saw the two former colleagues refuse to shake hands or speak to each other. They even demanded separate eating and toilet facilities. Petrosian went on to lose the match and was subsequently fired as editor of Russia's largest chess magazine, 64. His detractors condemned his reluctance to attack and some put it down to a lack of courage. At this point, however, Botvinnik spoke out on his behalf, stating that he only attacked when he felt secure and his greatest strength was in defence.

Some of his late successes included victories at Lone Pine 1976 and in the 1979 Paul Keres Memorial tournament in Tallinn (12/16 without a loss, ahead of Tal, Bronstein, and others) He shared first place (with Portisch and Hübner) in the Rio de Janeiro Interzonal the same year, and won second place in Tilburg in 1981, half a point behind the winner Beliavsky. It was here that he played his last famous victory, a miraculous escape against the young Garry Kasparov.

Personal life and death

Petrosian lived in Moscow from 1949. In the 1960s and 1970s, he lived at 59 Pyatnitskaya Street. When asked by Anthony Saidy whether he is Russian, Petrosian replied: "Abroad, they call us all Russians. I am a Soviet Armenian."

In 1952, Petrosian married Rona Yakovlevna (née Avinezer, 1923–2005), a Russian Jew born in Kiev, Ukraine. A graduate of the Moscow Institute of Foreign Languages, she was an English teacher and interpreter. She is buried at the Jewish section of the Vostryakovsky cemetery in Moscow. They had two sons: Vartan and Mikhail. The latter was Rona's son from the first marriage.

His hobbies included soccer, backgammon, cross-country skiing, table tennis, and gardening.

Petrosian died of stomach cancer on August 13, 1984, in Moscow and is buried in the Moscow Armenian Cemetery.